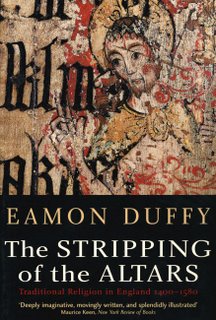

Eamon Duffy's major tome on religion in Pre-Reformation England is no mean read - and not just from the point of view of its length. The Stripping of the Altars is a major argument with previous historians of the English Reformation. But it is riveting and enlightening stuff.

Eamon Duffy's major tome on religion in Pre-Reformation England is no mean read - and not just from the point of view of its length. The Stripping of the Altars is a major argument with previous historians of the English Reformation. But it is riveting and enlightening stuff.Other writers had held (and it still has some degree of popular acceptance) that the English Reformation swept away a decadent and degenerate Roman Catholic English Church which was failing to bring the Christian faith to the masses.

Duffy (a Catholic himself) sets out to argue that the Catholic Church was vibrant, reforming and above all popular. He argues, along with many others, that the English Reformation was the unexpected result of Henry VIIIs political machinations, the largely unpopular dominance of his successor Edward's Protestant clique, and the early death of the Catholic Mary.

For those who have no idea what Pre-Reformation English Christianity looked like, in the first half of his book Duffy explains the role of the Mass, prayers for the dead, pilgrimages and the like. What emerges is a Christianity that seems gloriously colourful, often very piously focused on images of the suffering Christ and, with its cult of intercessary prayer to the Saints in some ways visually similar to Hinduism (for example statues decked with beads and clothing).

Some Christians might grit their teeth at this, but the first part of Duffy's work is simply a reminder of how other Christians have lived their faith. At points I found myself moved by the popular piety of the prayers many lay Catholics would have said and was led to reopen my copy of Julian of Norwich. At other times I was made to feel uncomfortable: indulgences for Purgatory are a difficult concept even for many Catholics.

In the second part Duffy looks at what really happened on the ground: how much did people really want to become Protestant? Historians now have the benefit of local documents, such as church wardens' reports, which can shed light on how individual church communities behaved. Though a few congregations did undeniably welcome royal decrees to, for example, remove images, most of these were urban churches in ports with connections to continental Protestant populations.

Many of the more rural churches dragged their feet when ordered to reform, hid images and crosses (which promptly reappeared when Mary revived Catholicism), and bent the rules as much as they could. Duffy reminds us that one has to bear in mind the significant fines and punishments that existed for disobeying royal orders to destroy Catholic relics and objects. But he also shows how much congregations valued their images, crosses and relics, often having paid large sums of money to purchase them, indicating the popular nature of much Catholic ritual.

Duffy's reading of history is a 'we was robbed!' one (as described by the Oxford historian, Christopher Haigh). According to Duffy few wanted the English Reformation, but with the length of Elizabeth's reign people and communities simply forgot what the past had been like: the memory was lost. Inevitably there are issues he skates over - he doesn't major on the effect of the Marian burnings, or the popularity of the Bible in English, for example.

Duffy's work then is something of a paean for a lost world. And reading his narrative of religious destruction (though he doesn't even treat the destruction of the monasteries) it's difficult not to feel wistful. How would churches look if they still had popular art all over their walls, if pews didn't clutter naves but left them open for communities to hold public events?

It is undeniable in hindsight that some of the aspects of the Reformation impoverished Christianity, slimming it down to a narrow focus on words only and no pictures (something we are gradually climbing out of again - how many Protestant churches now use art in Powerpoint displays to accompany sermons?). Many of the alternative worship events I have been to over the past years implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) draw on Pre-Reformation rites: lighting candles, using icons, going on pilgrimage, using water, wood and stone to pray with.

Ultimately the post-Reformation period under Elizabeth bequeathed a State Church which papered over the cracks of Protestant and Catholic, that left wiggle room for high and low alike. At this time, as an Anglican, it still seems clear to me that the ambiguous after-effects of the English Reformation and the deep psychological trauma it engendered are still very much a live issue.

(For those who might feel daunted by his tome, Duffy has written a shorter study of the effect of the Reformation in one tiny Church, called Voices of Morebath).

This book was on our reading list for the Tudor History module at college but our tutor did not recommend it because of Duffy's obvious bias. Interesting to read what you made of it.

ReplyDeleteI'm gald you found the review interesting. As an historian myself, I see 'bias' everywhere, no position is unbiased. I'm sad your tutor didn't recommend it, in fact I'm curious to know what s/he did recommend?

ReplyDelete