I was a guest at a 'grill a Christian leader' event a few nights ago at my church's youth group, Elements. Lots of very profound theological and philosophical questions: did God create us because he needed us - was God lonely? Does God love angels more than humans? Is God like me [the questioner]? Does God watch us like Big Brother? (And to kick it off: if God were a biscuit, what kind of biscuit would God be like?).

I was a guest at a 'grill a Christian leader' event a few nights ago at my church's youth group, Elements. Lots of very profound theological and philosophical questions: did God create us because he needed us - was God lonely? Does God love angels more than humans? Is God like me [the questioner]? Does God watch us like Big Brother? (And to kick it off: if God were a biscuit, what kind of biscuit would God be like?).One of the questions that we thought longest about was on the subject of intercessory prayer (doesn't God know already? why does God seem to intervene only intermittently?)

One insight we ran with for quite a while was the realization that in Hebrew the word for 'prayer' (tephillah) is reflexive. It technically means 'to pray to oneself'.

In this sense one might argue that part of the power of prayer is that it changes the person who prays.

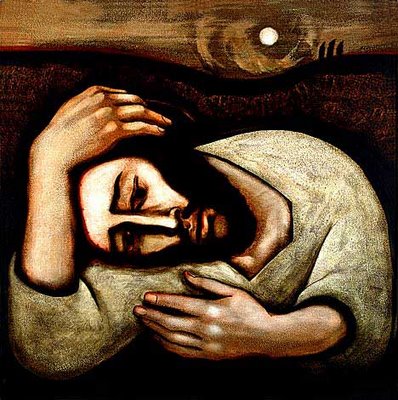

In this sense one might argue that part of the power of prayer is that it changes the person who prays.There's an example of this when Christ prays at his most extreme moment of mental agony, in Gethsemane. There he seems (as the Gospel writers tell it at least) to reuse parts of the prayer he earlier taught his disciples. "Let this cup pass from me, but not my will but your will be done" (cf. "may your will be done on Earth as it is in heaven...").

In other words, Jesus does ask God to bring about a change in the world, ("take away this cup...") but at the same time he offers up a change within himself to God ("but not my will..."). He is both attempting to 'change' God, but in the process he brings about a change in himself.

To those who ask, are Christians being optimists when they pray? The answer should be no: an optimist would only pray the first part of Jesus' prayer and assume that it will be accomplished ("I expect God to change the world, if I but ask!"). But neither are Christians pessimists: that would be to pray only the second part of Jesus' prayer ("I expect God to change nothing except me!").

Rather, Christians are people of hope. They are people who both dream of, and cry out for, a changed world. But they also accept that if that change is not presently able to occur, all is in God's hands anyway and our loving trust is to be offered regardless of the wider outcome. The answer to our prayer may - at least in the short term - be about us changing, not the situation we directly prayed for.

It was not just Gethsemane where this insight is realized. It is also witnessed to in the old story of Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-nego in the book of Daniel. As they are cast into the fiery furnace for not worshipping Nebuchadnezzar, they reply to the king's threat with words of hope (not optimism):

'If we are thrown into the blazing furnace, the God we serve is able to save us from it, and he will rescue us from your hand, O king. But even if he does not, we want you to know, O king, that we will not serve your gods...' (Daniel 3:17-18).

That kind of prayer (and that kind of faith) seems to me to be a long way from the triumphalism that often accompanies Christianity - and leads to disillusion.

1 comment:

That was beautiful; very insightful.

Post a Comment